The Fundamentals of Furniture Design: Finding Inspiration

Design inspiration is all around you, awaiting discovery. You just have to know where to look. It often turns up where you least expect it. You’ll find inspiration in nature. You’ll find it in the designs of others. Often, you’ll find inspiration in areas remotely related to furniture making. Be careful not to design cheap copies. A wise man once said, “originality is the art of carefully concealing your source”. For example, borrow the proportions of a classic design and apply it to a modern one. Take the moldings or ornamentation from your favorite piece of architecture and re-purpose it in your design. Don’t leave any stone unturned. Look everywhere for inspiration.

Nature

Inspiration is ripe in the natural world. You can borrow forms from both the animal and plant kingdoms. You can even take them from the microscopic world.

The spiral of a sea shell supplies inspiration for a table top. The shape of a pine cone reveals itself in the shape of the finials on a bed post. The natural world even influences the columns of the Corinthian classical order. Don’t stop at the basic shapes on forms. Nature also supplies ques for color, contrast, texture, and proportion. Living things aren’t the only source of inspiration in the natural world. Geology also supplies insight.

The Man-Made World

The men and women who came before us left design ques everywhere. Once discovered, use them in your designs in new and creative ways..

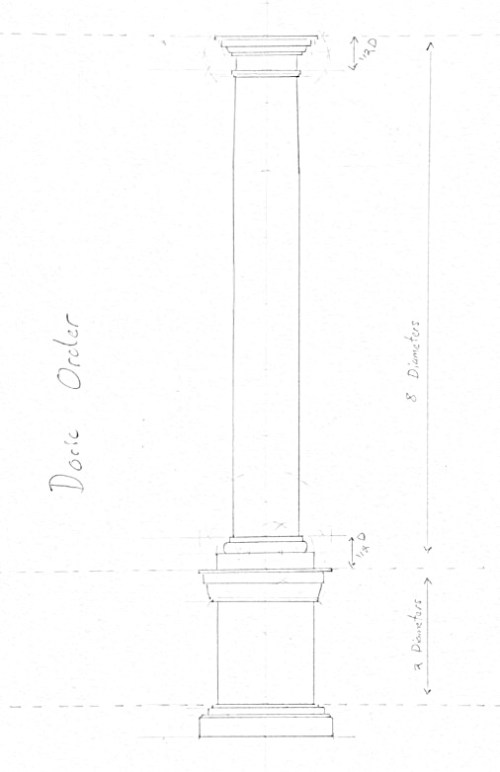

If you like cars, recreate the curves of your favorite model in a table or chair. Use the proportions of your favorite building in that chest of drawers you want to build. Boats, airplanes, temples, city layouts, even kitchen appliances: All great sources of inspiration for you next project. It’s okay to take ques from the furniture others have made. Just make sure that you keep it to an influence and avoid an outright copy.

Don’t forget to look past the shapes and forms you see. Look for details and takes notes.

Finding Design Inspiration on the Web

There are countless sources of inspiration on the Internet. A simple Google image search reveals page after page of material. Pinterest is a great source of inspiration (if you haven’t already, sign up for a free account and follow some furniture makers). There are countless design blogs to follow. YouTube is also an excellent resource.

To summarize, inspiration is found in many places that the average designer fails to look. Keep a notebook nearby and jot down anything that inspires you.

What is the most unusual source of inspiration you’ve seen used for a piece of furniture?

Fundamentals of Design: Series Index